January 8, 2018

Is the Socratic Method Right for Your Class?

Have you ever walked into a classroom where students were engaged in serious on-topic discussion, debating ideas and challenging each other to provide evidence of their statements? And when you looked around for the teacher, s/he was calmly sitting in the back, observing, taking it all in but not participating?

Have you ever walked into a classroom where students were engaged in serious on-topic discussion, debating ideas and challenging each other to provide evidence of their statements? And when you looked around for the teacher, s/he was calmly sitting in the back, observing, taking it all in but not participating?

Chances are, you entered a classroom using a discussion method known as Socratic Debate, aka Socratic Method, Socratic Circle, or Socratic Inquiry. Many teachers try this approach when they realize lecturing doesn’t engage students anymore. Sure, class members can memorize facts but too often the critical thinking required to analyze cause and effect — say, how a specific river encouraged ancient trade — eludes them unless the teacher spells it out, telling them the “right” answer.

In a traditional classroom, asking and answering questions is stressful to many students who are afraid their answer will be wrong. This is where the student-directed, no-right-wrong-answer Socratic Method shines.

What is it

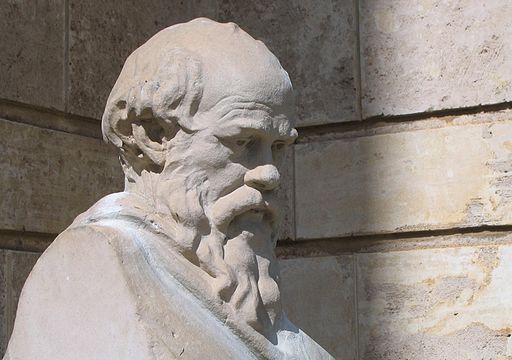

It all started with this (supposed) quote from the iconic Greek thinker, Socrates:

“Let us examine the question together, my friend, and if you can contradict anything I say, do so and I will be persuaded.”

This ancient form of give-and-take discourse is reportedly founded on Socrates’ belief that lecture was not an effective way to teach all students. The Socratic Method requires cooperative argumentative dialogue between individuals, asking and answering questions that stimulate critical thinking and draw out underlying presumptions. Students prepare by closely reading/researching the text or topic. On the day of the Socratic Seminar, they listen to classmates, challenge what they hear by building an argument based on what they have read and heard, and in so doing critically think about not only their opinions but those of classmates. This encourages listening, thinking, reading, speaking critically, and feeling a sense of wonder about the world’s knowledge. Students quickly figure out that to succeed in the Socratic Method, they must arrive prepared to share and listen and reflect.

Through this process, with subtle guidance from the instructor, students learn to teach themselves. Their goal is to analyze facts, not find the perfect answer. The Socratic Method is not passive. Students don’t consume; they create, participate, and gain a deeper understanding of the topic. The goal has nothing to do with who wins the argument but how evidence and ideas are presented.

How to use it in your Classroom

How to use it in your Classroom

- Remind students to arrive having prepared the required material.

- Set the stage for this questioning approach by discussing the power of questions in resolving issues.

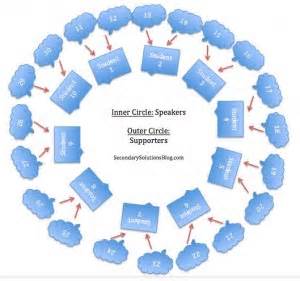

- Arrange students in two comfortable circles, the inner circle for talking and the outer for listening. These should be set up so students can see each other and interact easily. If the group is small, you may have just one circle.

- All students (and you) must know each other’s names, even at the first meeting.

- Set down conversation guidelines like 1) refer to each other by name, 2) participate by building on conversations, 3) participate often with comments and reactions to ideas of others, 4) don’t dominate the stage, 5) disagree, but don’t be disagreeable, and 6) wait your turn.

- Remind students there are no right or wrong answers.

- Remind students to focus on concepts and principles, not first person narratives. Personal experiences are fine, but they must be woven into the context of the conversation.

- As the teacher, you won’t be either the “sage on the stage” or “guide on the side”. You are part of a learning group.You pose well-structured, open-ended questions and then expect students to lead the discussion. Ideally, questions are not a stopping point but a beginning to further analysis and research.

- Keep the conversation on track — don’t let it veer in an entirely new direction without finding how that connects to earlier comments.

- Be comfortable with the silence. Students need time to think.

- Be comfortable learning from students. It’s not always clear where questions will end up.

Why it’s popular

One of the biggest reasons for the Socratic Method’s popularity is that it encourages and rewards higher-order thinking skills like evaluating, analyzing, and applying. These mindsets help students learn independently and develop them into life-long learners.

But it’s not only about sharing ideas. It’s about honing listening skills — deep listening. Students begin to love learning because it comes from themselves and peers. Students develop an understanding of the difference between arguing and discussing: The former is emotional; the latter while still impassioned, is respectful.

For Common Core schools, the Socratic Method prods students to:

- use text-based evidence to support their ideas

- identify and evaluate claims and counterclaims

- summarize points of agreement

- practice drawing inferences from texts

- initiate and participate effectively in a discussion

- pose and respond to questions that relate to the discussion

- prepare for a discussion on a particular topic

- practice using conventions of standard English grammar and general academic and domain-specific vocabulary when speaking

- gain understanding of other perspectives

What are its drawbacks

The Socratic Method wants teachers and students to follow a conversation where it goes. There isn’t a map with an X that the class gradually meanders toward. If the discussion goes far afield, so it does. It is well-suited to open-ended conversations such as “if a tree falls in the forest, does it make a noise”. As a result, and with a nod toward the constraints of curriculum and lesson plan goals, many teachers adapt the event and provide guidance in reaching the day’s Big Idea.

Second, it relies heavily on the understanding and knowledge of the group. If the students misunderstand a concept (like a Socratic Seminar I watched on “What is Capitalism“), then the conversation has little chance to arrive at the truth behind the questions.

Third, this approach works particularly well when students are learning about ethics, the philosophy behind an event, or the morals of a situation. Students must dig into their background to determine the motivations and assumptions behind their beliefs and then use that evidence to defend their thoughts. If/when that becomes impossible, likely the student adapts to a new reality.

Fourth, this approach is not quick. It relies on interaction between individuals, analyzing evidence, questioning everything, and being ready to change ideas.

Finally, this approach is not well-suited to webinars, a flipped classroom, or any other teaching method where students view resources without the opportunity to question them.

***

Though questioning beliefs can be a painful process, the Socratic Method includes two tools that make it effective: an open mind and respect for those around you. To provide this sort of gathering to students is a gift, arguably rarely seen since the amphitheaters of ancient Greece.

— image credit: Fresno Public Schools

— image credit: Secondarysolutionsblog.com and Wong, H.K., Wong, R.T. (2009) The First Days of School. Mountain View, CA: Harry K. Wong Publications, Inc.

–published first on TeachHUB

More on the Socratic Method:

30-min. video from Stanford’s School of Education

Socratic seminar in a 2nd grade Common Core class

A high school Socratic seminar explained

Jacqui Murray has been teaching K-8 technology for 20 years. She is the editor/author of over a hundred tech ed resources including a K-8 technology curriculum, K-8 keyboard curriculum, K-8 Digital Citizenship curriculum. She is an adjunct professor in tech ed, CSG Master Teacher, webmaster for four blogs, an Amazon Vine Voice reviewer, CAEP reviewer, CSTA presentation reviewer, freelance journalist on tech ed topics, and a weekly contributor to TeachHUB. You can find her resources at Structured Learning. Read Jacqui’s tech thriller series, To Hunt a Sub and Twenty-four Days.